My Father was not a voracious reader, but when he found a work he thought profound, he wasn’t shy about sharing it. One of his favorites was a scene in Ken Follett’s The Pillars of The Earth, the famous generational story of creating a cathedral in twelfth century England. Early in the book, William, a spoiled son of a nobleman, sacks a builder and his team once his fiancée spurns him, rendering an incomplete marital home pointless. Attempting to dismiss them without pay and depart on his horse, Tom, a builder and the book’s first protagonist, prevents William’s horse from leaving:

“William pulled on the reins, but Tom held the bridle tight, and the horse as distracted, nuzzling in Tom’s apron pocket for more food. “Apply to my father for your wages!” William said angrily.

Tom heard the carpenter say in a terrified voice: “We’ll do that, my lord, thanking you very much.”

Wretched coward, Tom thought, but he was trembling himself. Nevertheless, he forced himself to say: “If you want to dismiss us, you must pay us, according to the custom. Your father’s house is two days’ walk from here, and when we arrive, he may not be there.”

“Men have died for less than this,” William said. His cheeks reddened with anger.

Out of the corner of his eye, Tom saw the squire drop his hand to the hilt of his sword. He knew he should give up now, and humble himself, but there was an obstinate knot of anger in his belly, and as scared as he was, he could not bring himself to release the bridle. “Pay us first, then kill me,” he said recklessly. “You may hang for it, or you may not; but you’ll die sooner or later, and then I will be in heaven, and you will be in hell.”

The sneer froze on William’s face, and he paled. Tom was surprised: what had frightened the boy? Not the mention of hanging, surely: it was not likely that a lord would be hanged for the murder of a craftsman. Was he terrified of hell?

They stared at one another for a few moments. Tom watched with amazement and relief as William’s set expression of anger and contempt melted away, to be replaced with panicked anxiety. At last William took a leather purse from his belt and tossed it to his squire, saying: “Pay them.”

Some of this medieval scene resonates in the early months of 2025: a hereditary plutocrat stiffing his workers mid-construction might sound familiar, for starters. Yet what attracted my father, a devout Catholic, most to the episode was the power that one’s afterlife destination held in William’s psyche. William is fictional, yet his certainty of a judgmental hereafter – and fear of failing any such judgement – is grounded in an accurate historical assessment of what William Manchester called “the medieval mind.”

In A World Lit only by Fire, Manchester describes it thus:

“Heaven was above the immovable earth, somewhere in the overarching sky; hell seethed far beneath their feet. Kings ruled at the pleasure of the Almighty; all others did what they were told to do. Jesus, the son of God, had been crucified and resurrected, and his reappearance was imminent, or at any rate inevitable… The Church was indivisible, the afterlife a certainty; all knowledge was already known.”

Any understanding of the Middle Ages will color our thoughts of this mindset. We’re talking of course about one of civilization’s most violent and cruel periods, plagued with war, famine, and… well, plagues. Virtually no one alive today would trade places with a European living in the 1100s, regardless of their standing. Yet what that medieval Christian held as an asset, however dubious, that many of us do not is the certainty of the afterlife. For them, it was a thousand-year-old paradigm that brooked no disagreement; anything else was as inconceivable as planets beyond earth or vehicles that could travel without horses.

For all our modern innovation, Manchester argues at the end of his work that there’s a sadness in our view of the universe casting so much doubt on our ultimate destination:

“Worldwide there are now a billion Christians alive. Confidence in an afterlife, however, is another matter. The specter of skepticism haunts shrines and altars. Worshipers want to believe, and most of the time they persuade themselves that they do. But suppressing doubt is hard. Secular society makes it harder. Hardest of all is the sense of loss, the knowledge that the serenity of medieval faith, and the certitude of everlasting glory, are forever gone.”

It is against this backdrop – the divide between us and our ancestors about salvation or lack thereof – that leads to a consideration of the oath.

The early months of a year following an election cycle are fertile places to see media of our nation’s leaders taking oaths. Many of them become little more than stock images of politicians to be used for any various and sundry purpose when they make news. Others can be, shall we say, a bit curious:

The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart quipped that Trump’s hand wasn’t on either Bible during his swearing-in because “obviously one or the other would burst into flames.”

Oaths relate to our understanding of the afterlife and its consequences through their universal connection to religion. They pre-date medieval times, demanded of Roman soldiers, invoking Roman gods. Of course, knights swore oaths to their lords. Those who broke them were not only pariahs but considered guilty of mortal sins. Any Catholic will tell you that a mortal sin is serious business, in this life and the next. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, a mortal sin “destroys in us the charity without which eternal beatitude is impossible. Unrepented, it brings eternal death.” People who broke oaths were considered not just criminals, but at risk of losing their souls.

The more secular we have become, the less consideration we give to the moral consequences of breaking oaths, so much so that casual disregard for them seems an almost quotidian occurrence.

This brings us to our new administration’s cabinet confirmation hearings.

We’ll begin with Kash Patel. The newly confirmed FBI Director for the Trump administration has a history that certainly begs further study by the reader – anyone who publishes a list of “corrupt actors” working for the “deep state” needs careful examination before taking a position of authority inside of said state. But that strays from the point. What’s important is Patel’s behavior during his senate confirmation hearings – that time when he is speaking under oath. When asked by Illinois Senator Dick Durbin about whether he knew Stew Peters, an alt-right personality who has espoused antisemitic and white supremacist beliefs, Patel responded “not off the top of my head.”

Durbin reminded Patel that he had appeared on Peters’ podcast. Eight times.

On an internet broadcast, Peters claimed that he and Patel directly texted each other during a period when Patel’s “Fight with Kash” organization was suing Rolling Stone.

Democrats have, in their opposition to his confirmation, focused on this and other associations Patel has maintained over the years, such as Laura Loomer.

Patel’s friends – and writings – are disturbing and a good argument against his confirmation. But if we look at things from a more metaphysical perspective, a better argument is the almost bored perjury he committed.

It’s a difficult crime to prosecute – fewer than 300 federal cases per year are – but it is a crime, and in Patel’s case, one that’s visible from orbit.

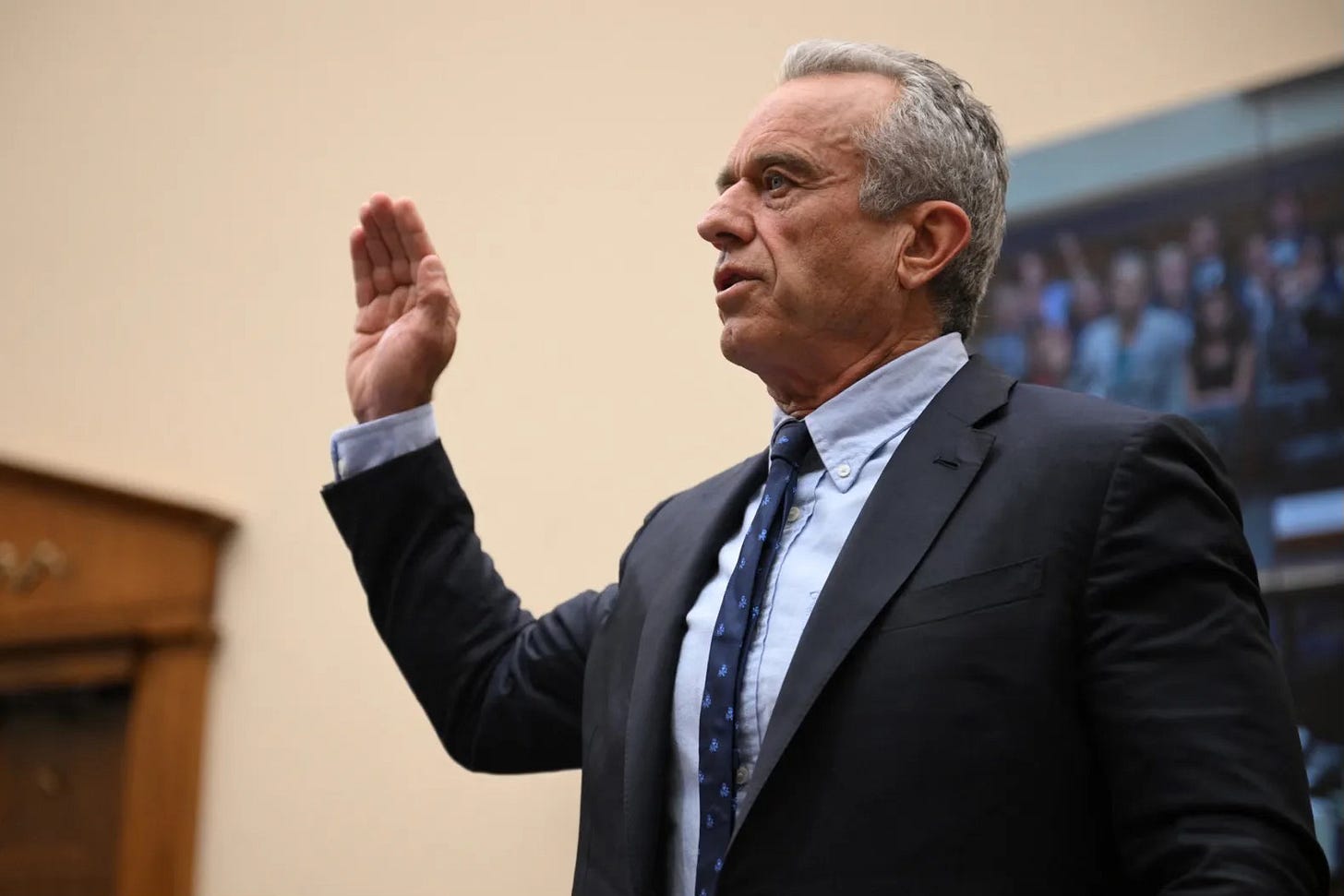

Next is Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Secretary of Health and Human Services. The New York Times reported the following during his opening statement, concerning accusations that he has been anti-vaccine:

“I am pro-safety,” Mr. Kennedy, President Trump’s nominee for health secretary, declared in his opening remarks. He insisted that he had been mistakenly labeled anti-vaccine in news reports, despite years of comments raising suspicions about the safety of inoculations. He was quickly interrupted by a protester in the audience who shouted, “He lies!”

He did.

Per the Associated Press, concerning an outbreak of Measles in Samoa in 2019:

“Samoa’s top health official… denounced as ‘a complete lie’ remarks that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. made during his bid to become U.S. health secretary, rejecting his claim that some who died in the country’s 2019 measles epidemic didn’t have the disease.

‘We don’t know what was killing them,’ Kennedy said during tense U.S. Senate hearings last week on whether he should oversee the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, suggesting that the cause of the 83 deaths — mostly of children under age 5 — was unclear.

‘It’s a total fabrication,’ Samoa Director-General of Health Dr. Alec Ekeroma told The Associated Press of Kennedy’s comments.”

Tests of the children who died in Samoa confirmed Ekeroma’s conclusion. Another oath, another lie.

It goes on. And on, and on, and on.

When we raise our hands in a courtroom or join them with our soon-to-be spouses in a church, or lift them in a military commissioning ceremony, we are not making a promise to the other people in the room. We are swearing to the divine that we will uphold our commitment to the truth, to our loved one, to our country.

It may seem naïve in 2025 to perseverate on the idea of failing to uphold a promise made to a God that close to half of our country doesn’t believe exists. Maybe so. But our founders believed that our constitution was grounded in the idea that there was a creator who endowed rights to humanity, independent of the whims of whomever was in charge.

If it is considered uncontroversial – even expected – to violate a promise made to our creator without consequence, what else is acceptable?

We’re beginning to see exactly what else the new administration is willing to do. Absent any moral dimension, everything becomes transactional. In exchange for his assistance in a crackdown on illegal immigration, the corruption charges against New York City Mayor Eric Adams have been dismissed “without prejudice,” meaning they can be revived at any time should the mayor fail to hold up his end of the bargain. The administration’s lackey, Associate Deputy AG Emil Bove III, has made this clear in no uncertain terms.

Those who are discomfited with this new (for America, anyway) approach are leaving in droves. The US Attorneys who refused to participate in dropping corruption charges against Eric Adams made honorable, noisy exits. Several of New York’s highest elected officials followed suit, in their case directly citing their oaths as reasons they could no longer continue serving the city.

In the past few days, we’ve seen our new transaction-only approach extend to our commitments to other countries. It is beyond the memory of most Americans that as part of the 1994 Budapest Memoranda, Ukraine relinquished its atomic arsenal in exchange for “security assurances” from the US and its allies. We made a promise to have Ukraine’s back in exchange for helping hold back nuclear proliferation. We broke that promise as early as 2014, though we at least made verbal assurances about honoring our commitments.

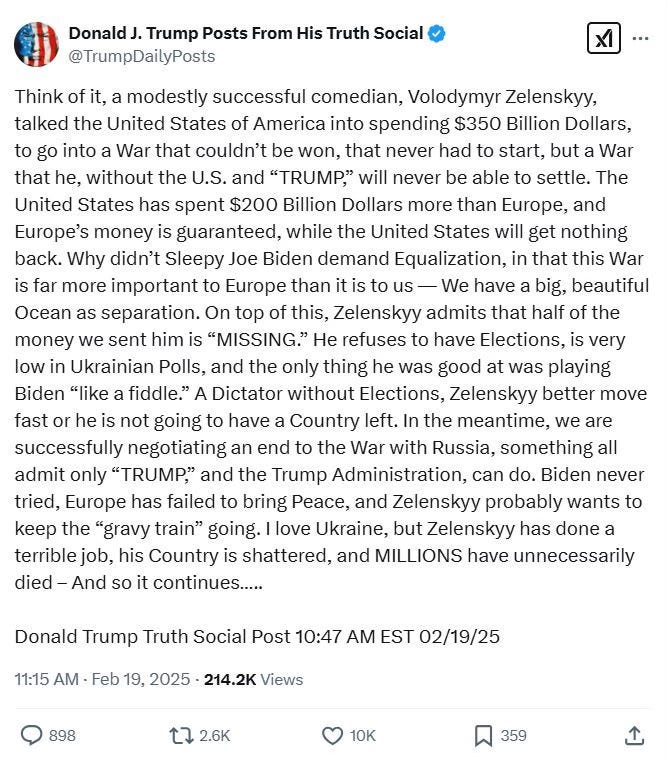

Today, there is no honor left even in our words:

Forget about fact checking any of this drivel. Of course, none of it is true. And why should it be? Why should we expect the man we elected to lead us to conduct himself with any sort of integrity or honor? Oaths are archaic, medieval inventions. What do we lose when we ignore them?

From John Adams’ Letter to the Massachusetts Militia:

“We have no Government armed with Power capable of contending with human Passions unbridled by… morality and Religion. Avarice, Ambition, Revenge or Galantry (sic), would break the strongest Cords of our Constitution as a Whale goes through a Net. Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

We are watching the whale break the net in real time.The question now becomes a simple one: what are we going to do about it?